Germany's Legacy Payment Tech And The Impact of AI

The world is changing fast is Europe keeping up?

Disclaimer: views expressed here are my own and do not represent any other organisation

Around 15 years ago, I lived in Germany for a couple of years. I’m feeling old right now saying that, but I really enjoyed my time living in the country, and I learned a lot. I learned that parts of mainland Europe loved cash - in a way that the UK, even back then, did not. I quickly noticed that in Germany most stores didn’t accept credit cards.

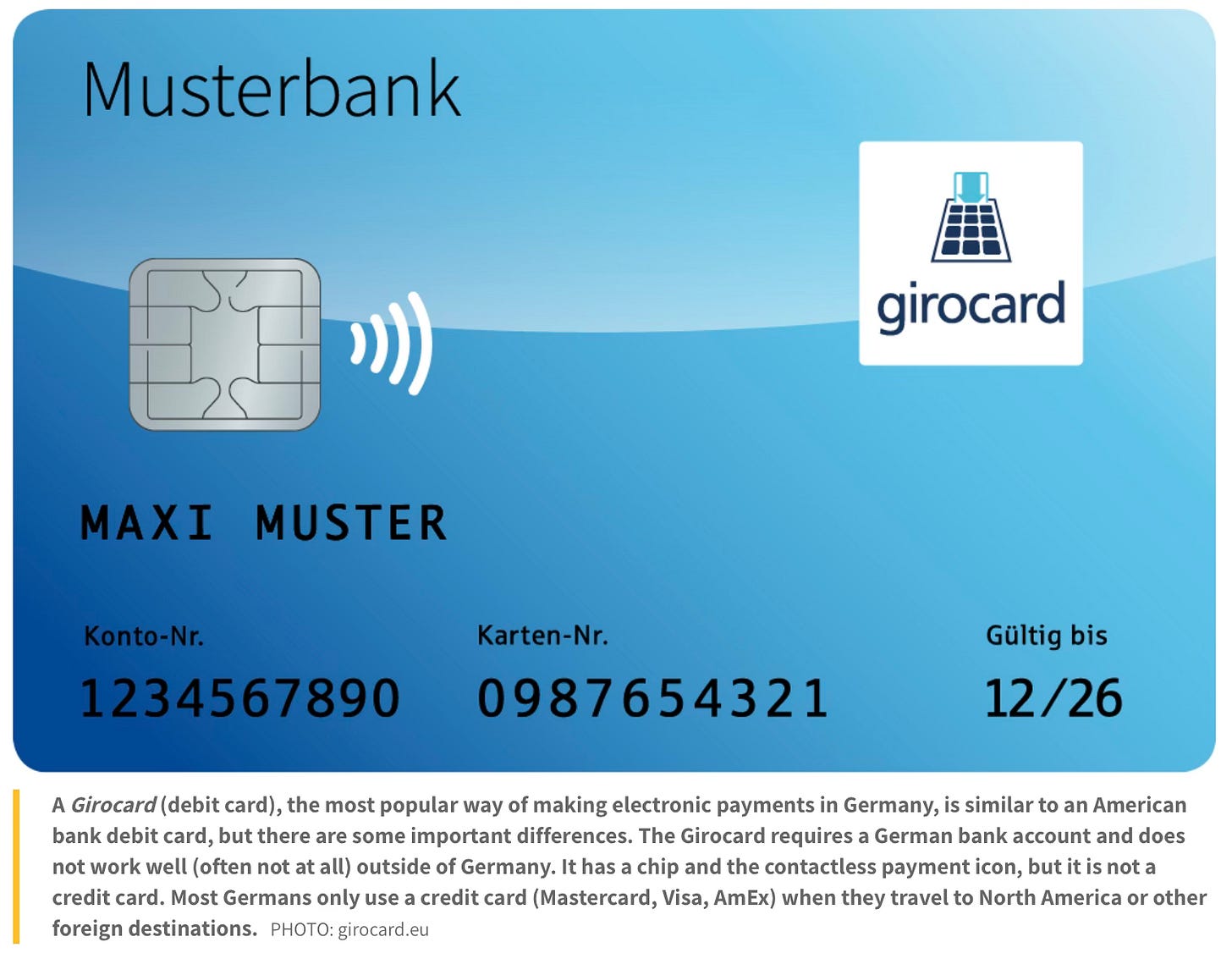

For most Germans, this wasn’t such an issue. With any bank account, Germans got, and still get, a Girocard. This seems like most other payment cards, but a key difference is that there is no long card number across the front of the card. (This long card number is usually called a Primary Account Number, or PAN, in Visa and Mastercard lingo.) Without the PAN, these cards can’t be used for online payments, yet they can be used for payments in-stores almost everywhere across Germany.

Girocard is the debit card of the German Banking Industry Committee. (In German “Die Deutsche Kreditwirtschaft”, often referred to as just DK). Founded in 1932, DK represents over 1,800 financial institutions, acting as a collective voice for various banking associations in Germany. Why did Germany embrace payments with Girocard but still, to some extent, shies away from international card brands? As is often the case, the answer is part culture, part market structure, and part regulation.

Payment Service Directive 2 (PSD2), harmonised, and capped interchange rates in European Union (EU) countries at 0.20% for debit cards 0.30% for credit cards. Corporate and business cards were not regulated, only consumer cards.

Before PSD2 came into force in January 2016, European countries had their own fee structures for card payment transactions, with large variations per country.

This delta was due to differing interchange fees, which account for the largest chunk of card payment fees. Prior to PSD2, the UK had an average fee of 1% for credit card transactions, but in Germany, fees were an average of 2%.

How interchange fees were set wasn’t transparent. Various organisations interacted to create each country’s fee structure, and only the end result was published to the payment processors and banks.

We can assume that German banks were interested in maintaining the status quo.

If fees for Visa and Mastercard stayed high (compared to the cost of accepting Girocard), then this would lead to less demand from businesses. In turn, less demand from consumers to get a Visa or Mastercard card from their bank. This dynamic suited many players in the German market, but would the alignment of fees across the continent change this dynamic?

With interchange fees aligning across Europe and reducing drastically in Germany, expectations were that card transactions from international card brands would grow. They did, but not to the extent many anticipated, and Girocard has held its position as the market leader.

Note: The UK used to have a similar domestic only payment card called Switch, but this got gradually replaced and swallowed up by Visa and Mastercard’s card brands, such as Maestro (Mastercard), and latterly Visa Debit, and Mastercard Debit. These days either a Visa or Mastercard Debit card is provided with every current account (checking account).

Attitudes To Debt

When I lived in Germany, in order to be able to pay online, I got a Mastercard credit card from my bank, Deutsche Bank. It cost €30 per year, and there was no option to pay only part of the monthly balance. Instead, it had to be paid in full at the end of the month.

This is quite different to the UK, the US, and Australia, where, for better or for worse, attitudes to debt are more liberal. One of the causes of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 was debt being given out too liberally. In the UK, there were cases, of new cards with set spending limits in the thousands of pounds being dropped through customers’ letter boxes read to be used.

This practice has not happened for a long time. But it’s still common for cardholders in the English-speaking world to choose to pay the minimum balance each month rather than the full balance, a practice which is extremely unlikely in Germany.

In the UK, Banks often compete with each other to win new cardholders by offering interest-free periods to new customers. And, of course, the biggest revenue generators are those who fail to pay their balance after an introductory period. Accumulating interest fees on debt can spiral, and be very costly if a user doesn’t manage their account carefully.

A Love Of Cash

One thing that many people who travel in Europe note is that Germany is still a society that likes cash. This study by EHI, showed that cash made up 35% of all retail payment transactions in 2024, just behind Girocard which made up 42%. Credit and debit cards made up less than 13% combined.

When it comes to Germans’ love for cash, Max Wolke, recently wrote an excellent post Why Germans love cash on his Substack shouldread, and noted:

Within living memory Germans have lived through two types of authoritarianism : fascism (Third Reich + Gestapo) and communism (DDR + Stasi). Both regimes used personal data to track, arrest and murder dissidents. This makes many Germans highly sensitive about what personal information they share, including transaction data. Cash, on the other hand, is anonymous and difficult to trace.

In Germany, what’s perceived as Datenschutz (information privacy) trumps other things, such as convenience or monetary gain. Paying by cash gives away as little personal information as possible. Even if paying by a credit card may have some benefits, such as rewards points or cashback, then it’s better to avoid this so that personal data is not put at risk. Local German data protection rules go beyond the EU’s already tough GDPR, and Germans are particularly careful about what they post on social media compared to other countries. To quote Max Wolke again:

The Germans have a well known saying that “nur Bares ist Wahres” (Only cash is true). This implies that the physical characteristics of cash make it more reliable, honest and truthful than digital equivalents. Having lived here for 6 years and having worked in more digitally advanced economies like the UK and USA, my personal view is that Germans are not early adopters of new fangled digital technologies.

This is definitely the case for payments. Germany has been a slow adopter of new payment technology. Much of the rest of the world is moving faster. Consider that:

In China, 15 years ago, most payments were made in cash. Today, almost every retail payment is made via a mobile wallet, namely Alipay or WeChat Pay. Cash can still be used as legal tender, but it rarely is these days.

In Indonesia, some businesses are now cashless. This means they only accept QR code payments via mobile wallets or from a banking app. Five years ago, this would have been unthinkable as cash dominated, but things changed quickly.

In Colombia, cash is still king - for now. But mobile wallets such as Nequí have been growing quickly. Half of Colombia’s adult population uses the app regularly.

Despite being one of the world’s richest economies, Germans still mainly use cash, or Girocard. That’s not to say that cash is bad per se.

(Above, I had initially described Girocard as “quasi-cash”, but to be clear, it is a debit card, albeit without any of the benefits that international card brands may bring, such as a chargeback system, rewards points, or being able to use it online.)

Cash can be a good thing. Many people argue that allowing cash payments is more inclusive. It can be easier to use for the elderly or those with learning difficulties, and cash is the best failsafe for when digital payment technology breaks down.

Yet the most important and most radical of any new technology is AI. Cash may not fit easily into a future where AI becomes a bigger part of our lives, including when it comes to payments.

The AI Equation

The past week has memorably seen the impact of the Chinese company DeepSeek, whose R1 reasoning model caused the share price of Nvidia to drop substantially. R1's success has prompted analysts to rethink the necessity of Nvidia’s high-end chips for future AI developments - at least to the extent previously anticipated.

R1 actually launched on the 20th of January, yet it took a week for stocks to react . It took time to assess the new model’s performance and to understand that the hardware it was trained on was not what would have been expected, given the model’s results on various performance benchmarks.

During the same week, President Trump, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son and Larry Ellison of Oracle got together to announce a $500bn investment in AI infrastructure. The project is known as Stargate, and the level of investment and ambition is quite remarkable. Although DeepSeek’s success took Stargate out of the news quicker than many had expected, it’s clear that the United States and China are the two world powers in AI right now.

There is a perception that the European Union is more concerned with regulating AI than with becoming a force in AI itself. Europe does have AI success stories such as Mistral AI, but a recent FT article asked whether Mistral AI has missed its moment.

Europe sits in its own space between the well-funded AI companies, primarily in the United States, and the Chinese innovators such as DeepSeek and Alibaba. (Alibaba’s Qwen 2.5-Max was released in the past days, and claims to be better than DeepSeek-V3, that R1 is based on.)

When it comes to payments, AI’s true impact has yet to be felt, but one aspect that warrants close attention is what has come to be known as Agentic AI. Until now, we could use Chat GPT to help plan a holiday. Just by asking, “Please plan a one-week holiday to Italy”, I can get a reasonably good travel itinerary presented to me. But I’d still need to go and book everything myself. All Chat GPT would do is provide the plan, not make it happen. With Agentic AI, we are getting closer to a world where AI will not just be able to plan an itinerary but actually book the trip for us, including making the required payments.

This does come with some challenges. For instance, how will a payment be authorised when no human is present for every transaction? In Europe, many purchases must be approved via two-factor authentication, such as via biometrics or a one-time password. Stripe has started looking at how this could work in practice, with their current option being to create a single-use virtual payment card with predefined parameters:

Use Stripe Issuing to create single-use virtual cards for your business purchases. This allows your agents to spend funds. The Issuing APIs allow you to programmatically approve or decline authorisations, ensuring your purchase intent matches the authorisation. Spending controls allow you to set budgets and limit spending for your agents.

It seems inevitable that as AI progresses, payments working alongside and with AI will also become the norm. Agentic AI will be a key emerging element in our lives and will automate all manner of tasks. Payments will keep evolving to consider how biometrics and authentication can work in a world where humans do less and machines do more. The obvious conclusion is that as Agentic AI progresses, the use of cash will become much harder to justify. Germany will need to lessen its reliance on cash to stay with the times. Will this finally be Germany’s impetus to change?

Great read, Matt! Last time I was in Germany, a coffee shop owner told me that cash is better than cards. I thought, yeah, right, mate—just like candles are better than electricity ;)

Great piece Matt. As a Munich resident and Oktoberfest regular I can confirm that cash is still very much king. I would love to model out if card payments would increase or decrease tips and the overall take. Drunk people being framed to tip 20% on a POS rather than the usual 10%? There’s a project there for someone…